UKSSN students and staff from across the regional networks were invited to read and review Peter Sutoris’ new book, Educating for the Anthropocene: Schooling and Activism in the Face of Slow Violence (MIT Press, 2022). Below you can read some thoughts on the book as a whole, followed by short reviews by three students and six staff of each section of the book.

“This book provides a bracing but nuanced view of environmental education and activism via the lens of ethnographic research conducted at schools in Wentworth, South Africa and Pashulok, India. Wentworth is the site of significant industrial contamination due to a nearby oil refinery, while Pashulok still reels from the huge impacts of the construction of the Tehri dam project and the pollution of the river Ganges. In both locations, students and the general population suffer the effects of what Sutoris describes as the ‘slow violence’ of rank environmental injustice. Through interviews with teachers and observation of guided activities such as documentary filmmaking, the author explores how practitioners often struggle to incorporate environmental themes into their strictly development-focused curricula. He also looks at the ways the often under-funded and ‘depoliticized’ education systems influence young people’s attitudes to earth care.

Although Sutoris makes clear that the book is not intended as a pedagogic guide, it should provide useful insights for practitioners interested in sustainability in education and decolonizing the curriculum. It also provides a sensitive and illuminating analysis of the often difficult relationship between activism and education.”

- Anna Orridge, Green Coordinator, Harris Federation

Artwork by Camille, a year 12 student from the London Schools Eco Network

- Artwork by Camille, a year 12 student from the London Schools Eco Network

Part I: Learning to Live in the Anthropocene

Dilemma 1: The Shock of Recognition: (DE)Politicizing Education

“From introduction to conclusion, Sutoris paints a scenic, coherent, yet analytical and rigorous picture of the multifaceted interactions between the layers of society that form any particular group, and, through the lens of climate policy, details the ways in which any policymaker must consider all of these variables in any potential plans. The ‘dilemma’ of the influence of politics on environmental education, explored here through the subtle nuances of the language employed in decision-making over school curricula, is detailed through a poignant, personal example, and draws in the readers’ curiosity towards how these ‘grave implications’ can affect all of us, worldwide. While exploring his own experiences, Sutoris makes a strong case for the prevalence of politics and politicization in education, yet is also careful to note the importance of fully understanding the various factors that combine to lead to such issues, and empathises with the individuals who have to raise – and act as role models to – children over whose futures they have fundamentally little control. Presenting the open discussion of over-politicization in the supposedly apolitical space of education not only as ‘worthwhile’ but also ‘radically practical’, we are left to wonder how this issue could have been left unexplored for so long.”

- Geza, Year 12 student, Manchester

Chapter 1: Introduction: Education's Task in the Anthropocene

“Busy teachers often don’t have much time to read challenging texts but maybe it is something that should be encouraged in light of the polycrisis we face. It feels that Peter Sutoris’ Educating for the Anthropocene is exactly the kind of book I should be reading. Sutoris’ research critiques the ways mainstream, state-run schooling fails to respond to the challenges of the Anthropocene and explores how activist movements may be able to fill the gaps left by schooling.

The book promotes critical thinking and gives a global view of the political, environmental, and social issues which have led us to this place in time. Reading it encouraged me to reflect on the work going on in my own classroom, am I educating ‘for sustainability’ or ‘with sustainability’? Am I actively encouraging change or simply continuing to support the status quo?

Educating for the Anthropocene is incredibly well-referenced which leads the reader to deepen their understanding with some challenging case studies and theories. Sutoris explains that we cannot expect education to solve the environmental crisis just as we cannot put the responsibility for solving the crisis on the shoulders of young people alone. ‘Education is not, nor can it ever be, the panacea, but it does have a role to play.’ The text asks profound questions such as ‘How may education enhance or hinder their ability to imagine and bring about alternative futures?’ Sutoris then explores the answers through the case studies of schooling and activism in two communities; Pashulok, a rehabilitation site of people displaced by the Tehri Dam in India and Wentworth, a community in the heart of the South Durban Industrial Basin in South Africa.For all its gloomy content, this book seeks to ‘illuminate the often unnoticed but important corners of hope where there is no space for oblivion’. Reading it made me beg the question, am I really preparing the children in my own classroom to have the courage and resilience they need to thrive in the Anthropocene?”

- Dr Meryl Batchelder, Science Teacher, Corbridge Middle School, Northumberland

Chapter 2: A Bittersweet Landscape

“Sutoris commences this chapter with the reflection that formal education is a crucial element of the forces that have permitted huge industrial projects to go ahead, contributing to our current ‘environmental multicrisis’. He asserts, however, that ‘we should not give up on education as one of the forces capable of transforming the future’.

He is critical of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, framing them as a tool of neoliberalism, as the ‘sustainability’ they aim for is inextricably linked with the push for economic growth, effectively a form of educational greenwash.

The author considers calls for a systemic transformation along socialist lines. He states that the problem ‘cannot be fixed by simply replacing one economic system for another’. This seems perhaps a little unduly dismissive, as he refers only to the Soviet model of socialism, which was indeed a regime of imperialist extractivism, but does not consider, for example, eco-socialism or anarcho-syndicalism as alternatives.

He reviews the work of relevant scholars who have studied the education/sustainability interface, highlighting the work of those who are critical of the ‘social reproduction’ model of Environmental and Sustainability Education (ESE), and explore the idea of the Anthropocene as ‘an opportunity to redefine what we mean by education’. Activist education, ecopedagogy and Indigenous perspectives on deschooling are outlined, with the author sounding a note of caution that not all communities have access to this traditional knowledge, and that we should be wary of ‘romanticizing and instrumentalizing’ Indigenous knowledge.

He ends the chapter with a reflection on Hannah Arendt’s and Paul Ricoeur’s theories, and the light they could shine on some of the most vexatious issues in ESE. Arendt’s analyses of ‘bureaucratization, agnostic pluralism and politics’ have particular relevance to formal education. Ricoeur’s ideas about the writing of history as payment of a ‘debt’ to the dead can be extended to environmental destruction, which could be conceptualized as a ‘debt to the not-yet-born – a debt impossible to pay’.”

- Anna Orridge, Green Coordinator, Harris Federation

Artwork by Camille, a year 12 student from the London Schools Eco Network

- Artwork by Camille, a year 12 student from the London Schools Eco Network

Part II: Schooling on the High Anthropocene’s Frontier

Dilemma 2: Representing Liminality: Total Institution or Tough Love?

“Sutoris tells the story of a boy who was a troublemaker at the school where the author worked in South Africa. He explained that the violence of his home life influenced him to bully others. He uses this story to show how the boy stopped antisocial actions when Sutoris’ colleague Meghan let him express and explain himself.

Sutoris asks ‘Were the teachers agents of an institution or activists in their own right, battling the legacies of apartheid by trying to bring out the best in these children?’ His example shows that Meghan was trying to bring out the best in the children in contrast to other teachers who did not think that students could have any desire to learn.

He also asks ‘Where did the influence of bureaucratisation and depoliticization end and caring individual agency begin?’ This dilemma sets up the question of how schools can move away from being rigid and controlled by central government towards a system that can adapt to the needs of society in an environmental context to give children the tools they need in the changing world.

I think that the way Sutoris uses storytelling makes reading feel more personal, however some of the details seem unnecessary. Reading it made me think more about how education systems are shaped by political context.”

- Camille, Year 12 student, Hertfordshire

Chapter 3: The Origins of Depoliticization

“In this chapter, Sutoris considers the way in which the Indian and South African education systems have worked to prepare citizens to carry out certain tasks, in accordance with the plans of central government, rather than politicizing them. The concept of politicization which he deploys here is drawn from Hannah Arendt, according to which being politicized means being prepared to carry out creative acts of self-realisation in the presence of others, and the relative absence of such self-realisation is, as Sutoris sees things, an obstacle to action which might alleviate the climate and environmental crises.

The focus on India (Pashulok) and South Africa (Wentworth) is illuminating, Sutoris believes, because the countries are experiencing an acceleration of the slow violence that forms one of the central themes of the book. Because of this, they may be useful bellwethers of what other countries will experience in the near future.

In the Indian case, Sutoris focuses on the way in which post-independence India has embraced industrialisation and economic growth, with little regard for environmental protections, and the links between this and the earlier colonial history of the country. In the South African one, he focuses on how the transition from apartheid to post-apartheid involved a focus on economic growth and foreign investment rather than on repairing the environmental damage done, often through aggressive resource extraction in an earlier period of South Africa’s history.

At the same time, however, Sutoris draws attention to the way in which depoliticization (in the relevant sense) appears to be operating in both locations despite the differences between Pashulok, which he describes as ‘peripheral’, and Wentworth, which he describes as ‘happening’. The implied moral of the chapter is that obstacles to environmental action which need to be overcome by educational reforms can exist in a variety of different national contexts.”

- Dr Gabriel Roberts, Teacher of English and Environmental Sustainability Researcher and Project Officer, Highgate School, London

Chapter 4: Reading the Cultural Landscapes of Schooling: Depoliticization and Hope

“Writing in a technical style not immediately accessible, in this chapter Sutoris describes his research into how students in India and South Africa think about their environment. Despite the dense, anthropology paper format, he manages to evoke a clear feeling of the strictures that modern education systems seem to impose upon teachers and students alike.

Sutoris discusses how he finds that a ‘drive towards development [means] losing out on moral and traditional values’, suggesting that any sustainability focus there may be is very much focused on individualisation, rather than systemic change.

His findings in both India and South Africa show similarities to UK schools, in that while environmental education is much talked about, there is no training for it, teachers don’t take it seriously, and it is either taught by rote from textbooks, or as a ‘relaxation’ subject where students get to enjoy being outside. Lessons are more often than not given up to other essential school tasks. There is a perception that there is no point studying environmentalism because it doesn’t lead to qualifications that will further a student's life chances. He describes a system – seemingly designed to perpetuate what he calls ‘slow and fast violence’ on communities – that promotes an idea that with hard work you can overcome society's ills, rather than imagining that we could develop societies without such ills.

The pace of the chapter picks up when he describes the outcomes of his film-making projects, where students show deep awareness of Anthropocene issues, and a desire to communicate imaginatively across generations. He derives hope from ‘outlier teachers’ who do their best to inject environmental justice concerns into the curriculum; teachers working to ensure students are given the tools to stand up for what is right and have a voice. He found hope in the fact that students were obviously keenly aware of the injustice being done to them by the ‘slow violence’ of industrialised environmental degradation, and notably that the work of relatively few activists seeking to improve this situation was making a difference. This gave me a strong feeling that, while sometimes it may feel as if we are lone, small voices in a very large crowd, the work we do and efforts we go to are well worth it. The influence we have goes far beyond what we can realise or imagine.”

- Mary Leonard, Science Teacher, Worle School, Somerset

Artwork by Camille, a year 12 student from the London Schools Eco Network

-Artwork by Camille, a year 12 student from the London Schools Eco Network

Part III: What is the Alternative?

Dilemma 3: The Myth of Impartiality, or How I (Almost) Became An Activist

“From the small part of the book that I have read, I found that the experiences that the author went through for his research to be most challenging for his ethics and own personal politics. I found it truly intriguing to read about the psychology behind activism, not something that immediately comes to mind when discussing it. In fact, many don’t usually hear about the internalised, more negative parts of activism, such as the control that the writer put himself under to see the broader opinions from others. I found the read a fascinating one, which allowed me to see activism beneath the surface level.”

- Grace, Year 11 student, Hampshire

Chapter 5: Environmental Activism: An Answer to Educating for the Anthropocene?

“In this chapter, Sutoris immerses readers in the analysis of how ‘understanding the implications of activism for education in the age of the Anthropocene requires exposing the cultural and ideological landscapes of activism’ and how agonism proves to be an essential ingredient in education, especially when promoting youth activism.

When developing his research in India and South Africa, through the anti-dam activist in Pashulok against the development of the Tehri Dam and the anti-pollution activist in Wentworth, South Africa, it becomes evident that action is at the heart of activism. However, action is not promoted in formal education, as it may clash with the principles school promote.

The analysis of the discourses that Sutoris develops with activists in Pashulok and Wentworth takes him to define two modalities of agonistic pluralism that are a prerequisite to Arendtian politics that underpin the evolution of both environmental/social movements. Anti-dam activism, in Pashulok, can be defined as a vertical or intergenerational agonistic pluralism that develops existing ideas of the future from what was the past and how that future can look from that perception for the unborn lifestyles. The anti-pollution activism in Wentworth can be framed in what is defined as horizontal or intergenerational agonistic pluralism, which brings together citizens to act, finding common solutions even if they have different identities (race, beliefs, class, language, ethnicity, gender). Both modalities are crucial to taking action and provide the necessary ingredients to act with others. Sutoris acknowledges that these modalities have their joint action in what he calls vertical-horizontal agonism.

This chapter is a clear demonstration of how social movements are intrinsically related to a desire for social and environmental change. It reflects the faith that people collectively can bring about or prevent change if they dedicate themselves to the pursuit of a common goal.”

- Ana Romero, Head of Sustainability, Wellington College, Berkshire

Chapter 6: Toward a Different Anthropocene Politics

“The mention of Arendt (1998)’s thinking struck an immediate chord as Sutoris described the mental world of Homo faber (‘Man the maker’) human beings who believe it is possible to control the environment and their fate through work, a process that sees everything in the world as a means to an end, producing a disconnect from others, significant parts of our own selves and the Earth on which we live. A scene repeated across UK schools up and down the country and one of the very reasons there is a disconnect between schooling and activism. Indeed, bridging the gap between schooling and activism would provide positive change, but is their room in the overpacked curriculum presented by overworked teachers where there is not time nor capacity for thought? Only the brave leaders make the room in their school for this. For most, pupils are vessels which are filled and expected to react, recall and persistently prove they can remember. ‘Discipline itself repeats the misguided belief it exists’.

Activists have a role if the young people are empowered to question and think, along with the educator. Small pockets of environmental or social justice do exist, in Eco Groups, Debating Societies, Christian Unions (was Jesus the best activist?) which inadvertently use the grasp, care, imagine, communicate model Sutoris suggests.

My own experience has found the young activist to be one of two types, a privileged child who has everything, so few worries, or the child with nothing and nothing to lose, who may find a strand of common ground with those in Delhi, Durban or other post-colonial lands, cited by Sutoris.

Indeed, the label of ‘activist’ can be connected to a plethora of sociocultural and economic issues. Schools should find polyvocal opportunities for children to be empowered to find their own cause. Until the education landscape is reimagined in England, then Sutoris’ findings will be left on the shelf. The intergenerational flow of information has turned to a trickle and radical imagination constrained to almost nil, as the arts are squeezed from the curriculum. Whilst I agree that education shouldn’t be for social engineers, ‘Replac[ing] the individualism of our consumer society with a recognition of our shared humanity’ should not lead to centralised control by a queen bee over individual children’s thinking. Indeed, the activist should be breaking the mould and off scouting for a new hive.”

- Wendy Litherland, Assistant Headteacher, Accrington St Christopher’s CE High School and Sixth Form, Lancashire

Author Peter Sutoris

Contact

If you would like to know more about Transform Our World, or any of our programmes, please get in touch.

Thank you for submitting your enquiry! We are currently receiving a large number of enquiries and are trying our best to get back to people as soon as possible. In the meantime, you might find one of the following links helpful:

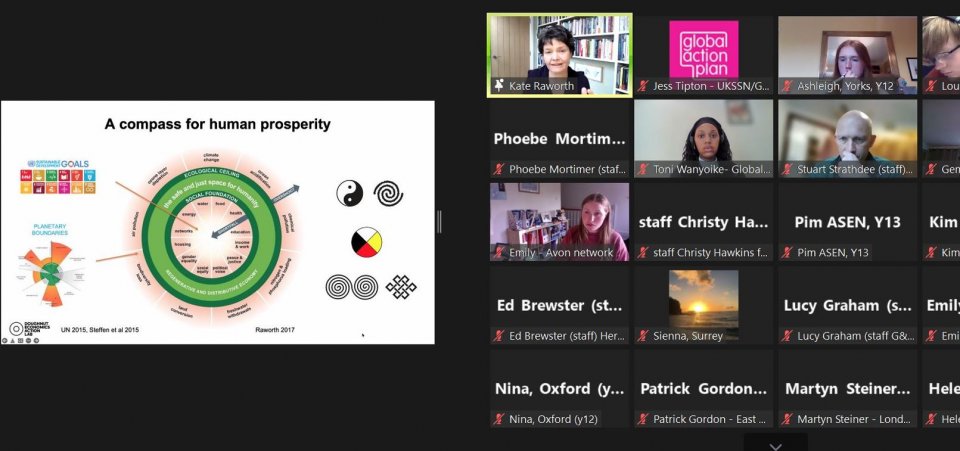

Access catch up content from the Transform Our World Youth Summit

As a Transform Our World user, you can access the content from the Transform Our World Youth Summit and catch up on the content across three themed days, looking at individual actions we can do, people in power we can influence and the importance of living our true values.

Follow the links below and check out the timestamp guide to navigate the content.

- Are you a teacher? Learn about how to use the website here.

- Looking for teaching resources? You can find our collection of highly-rated resources here.

- Looking for something more long-term? Check out our featured programmes here.

- Want to see what other schools have been up to? Have a read of some case studies here.

- Alternatively, take a look at our FAQs and About pages as they might help to answer your question(s).

All the best,

The Transform Our World team

is brought to you by